A Cultural History of Disability in the Middle Ages by Jonathan Hsy;Tory V. Pearman;Joshua R. Eyler;

Author:Jonathan Hsy;Tory V. Pearman;Joshua R. Eyler;

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: Bloomsbury UK

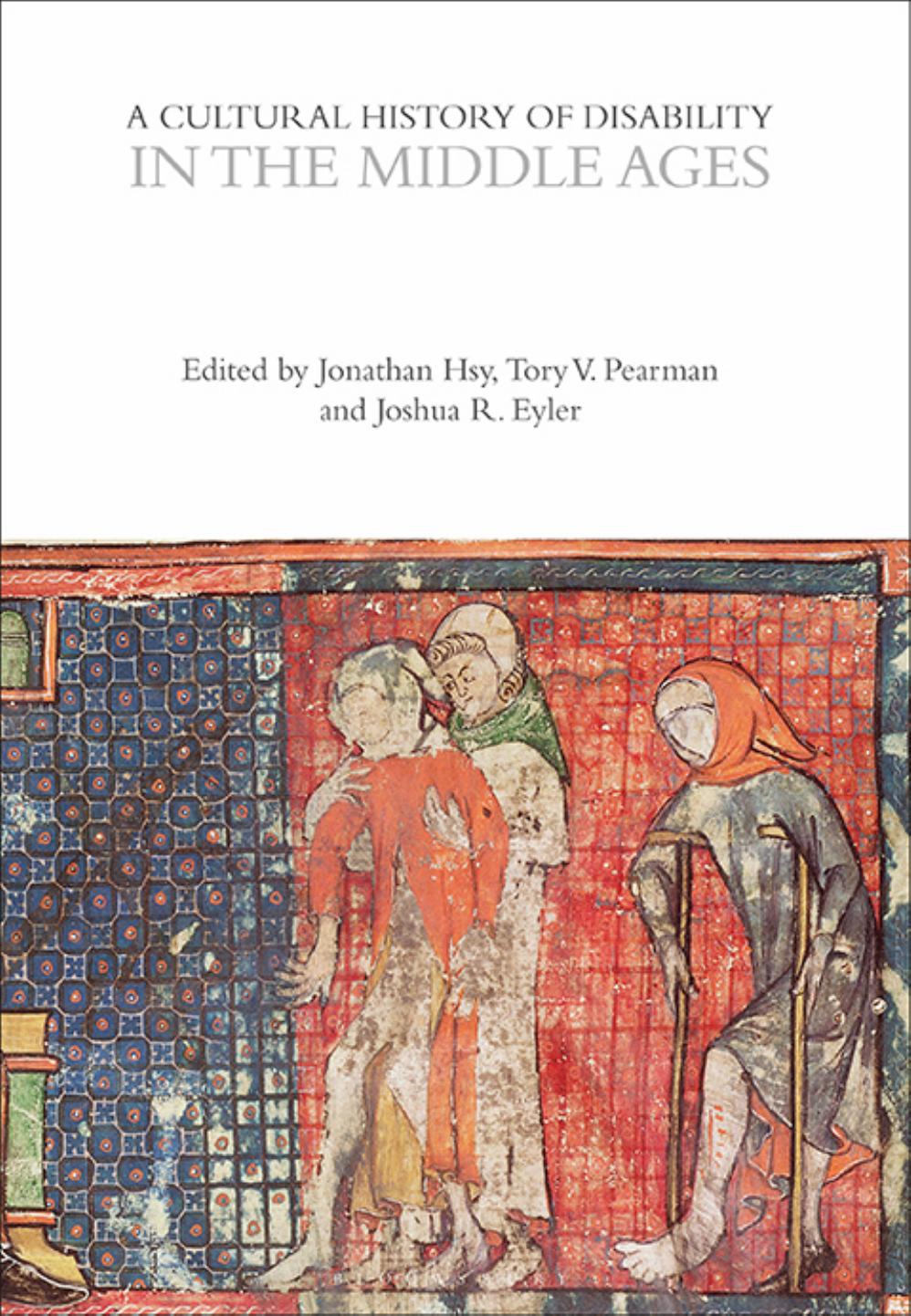

FIGURE 5.1 Fifteenth-century German Expositiones evangeliorum representing Christ healing a deaf man and sticking his finger in the manâs ear. Klosterneuburg, Stiftsbibliothek, Codex Claustroneoburgensis 4, fol. 114v. By permission of the Augustinian Canonry Klosterneuburg, Library. http://cdm.csbsju.edu/digital/collection/HMMLClrMicr/id/16400/rec/1

FIGURE 5.2 An unheeded marginal instruction to the illustrator in a copy of Jean Corbechonâs French translation of De proprietatibus rerum. Paris, BnF MS fr. 22532, fol. 102v. By permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The limited iconographic possibilities for the representation of deafness reflect the difficulty of diagnosing conditions that, while physiologically explained by humoral theory, betray no visible, external signs. As in the literary texts that render deafness more visible by pairing it with other conditions, some works represent deafness through visual analogy with other, more easily represented impairmentsâthough these strategies can also highlight deafnessâs interpretive ambiguity. In the Bodmer manuscript of René dâAnjouâs Mortifiement de vaine plaisance, for example, an allegory of a cart drawn by blind and deaf horses is illustrated with an image of two horses, one blindfolded and the other with a band tied around its head and covering the ears (René dâAnjou 2009: 33v): the blindfoldâs use as a conventional visual shorthand for blindness is what allows the reader to interpret the other band as a signifier of deafness. A similar representative strategy is employed in the roughly contemporaneous morality play Excellence, Science, Paris et Peuple, whose dialogue makes it clear that the actor playing Paris must have been accoutred with a similar signal of deafnessâthough this one proves more ambiguous. Science initially presumes that Paris is deaf because he has a kerchief tied around his head; Excellence, observing the same fact, presumes that Paris must have a toothache. Through this ludic dispute, we see both the inherently ambiguous visual representation of deafness and the social dimension of its diagnosis. Deafness offers no telltale visual markers; it can only be diagnosed, tested, or confirmed through failed attempts at dialogue or provocation.

As Edna Edith Sayers has noted, âdeafness in any narrative presents the author or storyteller with a most difficult challengeâ (2010: 87). Medieval literary texts often display considerable anxiety about not only the difficulty of representing deafness, but also the impossibility of a visual diagnosis of auditory impairment, and the ease with which deafness can be feigned. In addition to Boccaccioâs tale of Masetto da Lamporecchio, whose plot centers on a simulated disability, episodes of feigned deafness also occur in sources as varied as the thirteenth-century Icelandersâ saga Laxdoela saga, in which the Irish princess Melkorka feigns deafness and muteness and is sold as a slave (Bragg 1997a: 173); the early thirteenth-century Arthurian romance Daniel von dem Blühenden Tal (Daniel of the Flowering Valley) by the Middle High German poet Der Stricker, in which the hero feigns deafness in order to defeat an adversary18; and George Chastellainâs Burgundian Chronicle, which devotes a chapter to a fraudulent seer posing as a deafâmute in Ghent in the 1450s, while also alluding to a similar case in Portugal (1863â66: 3.298â300). These

Download

A Cultural History of Disability in the Middle Ages by Jonathan Hsy;Tory V. Pearman;Joshua R. Eyler;.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Books & Reading | Comparative Literature |

| Criticism & Theory | Genres & Styles |

| Movements & Periods | Reference |

| Regional & Cultural | Women Authors |

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11919)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7520)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(6897)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5434)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(5421)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5041)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4714)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(4671)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(4498)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4321)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4313)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(4225)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(4170)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(3872)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(3857)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(3791)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(3787)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3752)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3650)